Which are the arguments and how many are there? I must have an inbred urge toward symmetry. In canvassing for the principal ways of criticizing, assaulting, and ridiculing the three successive "progressive" thrusts of Marshall's story, I have come up with another triad: that is, with three principal reactive-reactionary theses, which I call the perversity thesis or thesis of the perverse effect, the futility thesis, and the jeopardy thesis. According to the perversity thesis, any purposive action to improve some feature of the political, social, or economic order only serves to exacerbate the condition one wishes to remedy. The futility thesis holds that attempts at social transformation will be unavailing, that they will simply fail to “make a dent.” Finally, the jeopardy thesis argues that the code of the proposed chafe or reform is too high as it endangers some previous, precious accomplishment.

The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy (1991)

The planet is on fire.

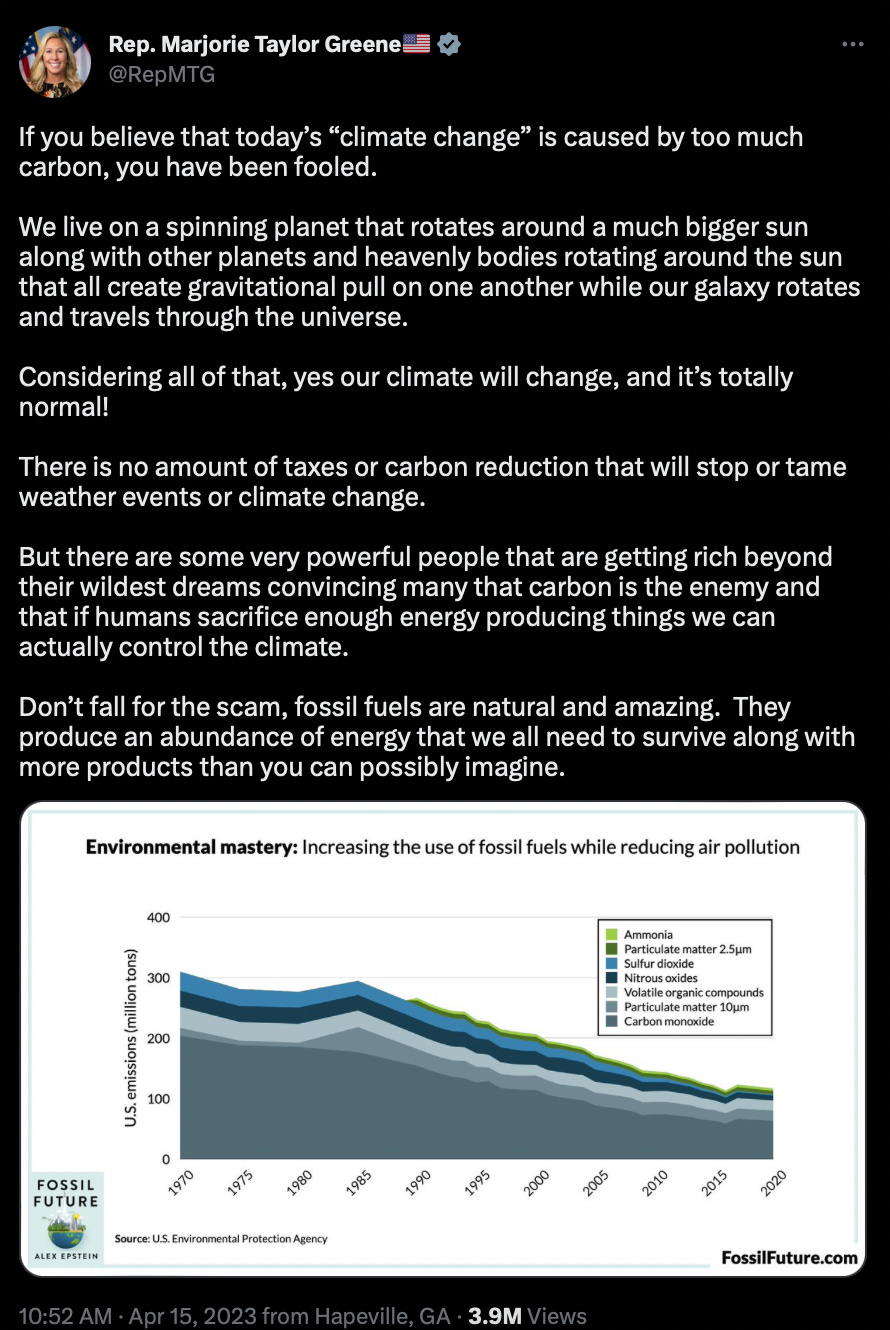

Despite knowing why, political discussions today, especially those in the richest and most developed nations on Earth, still tend to debate over the extent of human involvement in the evolution of the world’s climate. One of the best examples of this is a recent Tweet by the American nationalist politician, Marjorie Taylor Greene:

Now, if you’ve been paying attention, you’ll notice what’s missing from the above graph - the level of CO2 in the air. As you can see here, MTG uses a variety of strategies to spread uncertainty and doubt about the reality of climate change and climate mitigation. What is quite interesting is how many of these strategies map onto rhetorical strategies mapped out by the economist Albert O. Hirschman in his book The Rhetoric of Reaction:

She attributes large epochal shifts in the global climate to merely natural forces alone, arguing that the Milankovitch cycles are really what is driving major climate shifts. This is a claim that many climate change skeptics love to make, but it’s a claim that refuses to listen to scientists arguing that these shifts alone cannot and will not explain the huge divergence in widespread climate shifts. This is the perversity thesis - the idea that addressing an issue will only exacerbate things worse - here, the argument is that by addressing climate change, we’re only attempting to make natural cycles of climate transformations worse.

The next strategy that MTG uses is attempting to argue that no number of policies or climate change. This is obviously wrong, given that if we reduced the amount of carbon in the atmosphere or reached net zero in the next decade or so, we would reduce the chances of global warming above 3 degrees Celsius. This is the futility thesis - the idea that even if we wanted to, addressing climate change would be futile given we don’t know what to do or how to solve this issue in the right way.

Lastly, MTG argues that if we reduce our reliance on carbon production, we would give up all our creature comforts in order to benefit some shadowy elite group that ones to control us all and reduce us to the standards of bare living. This is the jeopardy thesis: the idea that if we address an issue, we will give up the high standards of living we’ve grown so used to as a fact of life.

Greene is not the only one making arguments relying on the various strategies outlined by Hirschmann - Canadian psychology professor Jordan Peterson’s engagement with climate change here and here also rely on the rhetoric of reaction in order to muddy the waters about attempting to resolve the climate crisis.

Peterson argues that “we must seperate the science from the politics”: a task for fools. Politics is the art of living together, is it not? Given that the global climate regime is an indictment of how we are (currently) living together, how could it be anything other than being political? A constant refrain by climate skeptics and denialists is that we must somehow seperate politics from science, but this neglects to realize that science is not produced or created within a vacuum: to argue otherwise would be to return to a form of positivism abandoned years ago for good reason.

Peterson also argues that given the level of uncertain impacts on the climate, we would be better suited towards addressing other global concerns. What Peterson neglects to mention is how many of those global concerns would be much worse off in a world that is 3-4 degree C hotter.

A world in which global disease runs rampant seems at odds with Peterson’s desire for the ability of human brainpower to resolve the issue of climate change, but it makes sense if you look at Peterson’s argument through the lens of Hirschmann: “Why should we deal with climate change now if it’s only going to make things worse in terms of resolving other global issues?”

One can trace back Peterson’s thoughts here back to the statistician and climate skeptic and/or denialist Bjorn Lomborg who argues that addressing climate change is probably one of the least effective ways at increasing global welfare and that focusing on climate change would probably make things worse off instead of focusing on global development: once again, a great example of both the perversity and jeopardy arguments in action! What is fascinatingly neglected by this argument is how carbon intensive rapid growth is going to be and the need for countries to figure out pathways of both deep decarbonization and development while remaining within planetary ecological boundaries - if every developing nation adopted the carbon-intensive industrialization patterns that Western nations did in order to grow, it’s a real possibility that we will shoot well beyond our ecological breakpoint as a result, stuck between poles of trying to maximize economic well-being and trying to retain a livable planet.

Once you start looking for examples of rhetoric of reaction, you can find them almost anywhere when it comes to the climate debate - these two videos are great example. See if you can determine which strategy is being used here and here:

These arguments and rhetorical strategies in use here are nothing new: they are the extension of conservative arguments transposed for a new era, one where their usage is used to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt about the reality of global climate change and human involvement in perpetuating an organization of living and production that relies on a high cost on the biosphere. But tracing this back to a specific rhetorical strategy by conservatives isn’t enough to explain the affective investment many have to the the current carbon producing regime - how did climate change denialism become part of a strand of what seems to be an increasing trend in conservativism anti-intellectualism?

Attributing it to material interest alone (which cannot be disputed in a critical analysis of why climate change is so hard to mitigate) doesn’t explain why so many who have never had any sort of material relationship with the carbon-intensive sectors of the economy are so reluctant to admit the reality of the climate crisis. The best factor to explain this, I believe, has been culture and social psychology.

Andrew J. Hoffman has written an excellent book on climate change and how cultural psychology shapes reception of it entitled “How Culture Shapes the Climate Change Debate”. Hoffman argues that the cognitive filters and underlying ideological underpinnings shape how we engage with issues with climate change - so far, this sounds like fairly obvious stuff. Where Hoffman is quite interesting is pointing out how increased knowledge doesn’t really matter in trying to convincing people about the reality of climate change; the above videos are a great example of this in action - people who are professional scientists end up convincing themselves into climate denialism as a result of their ideological cognitive filters and beliefs, and this hyper-polarization on climate change makes it close to impossible to figure out how to address the ecological challenge before us. Moving towards a position where we ideologically depolarize the existence of climate change would be ideal, but given the vested interests pushing for high levels of polarization, what degree of depolarization can be accomplished? Hoffman suggests moving away from narratives that are tied to one political side, but the challenge here is how far can you do so without losing sight of the underlying reality of the limits of the biosphere. What happens in a world where people would rather be first class passengers on a sinking ship as opposed to building a commonwealth for all?

What, then, is to be done?

Sharon, I deny that you will read this.

Finally got around to reading this and it's an excellent first (proper) post. The underlying concept is succintly explained and it's certainly something I'll be looking out for in the future.

Couple of odd/missed words here or there but it didn't detract much from the overall post - I'd always suggest putting stuff in front of a second or third pair of eyes as well as triple-checking yourself (although you might have already done this, in which case ignore me.)